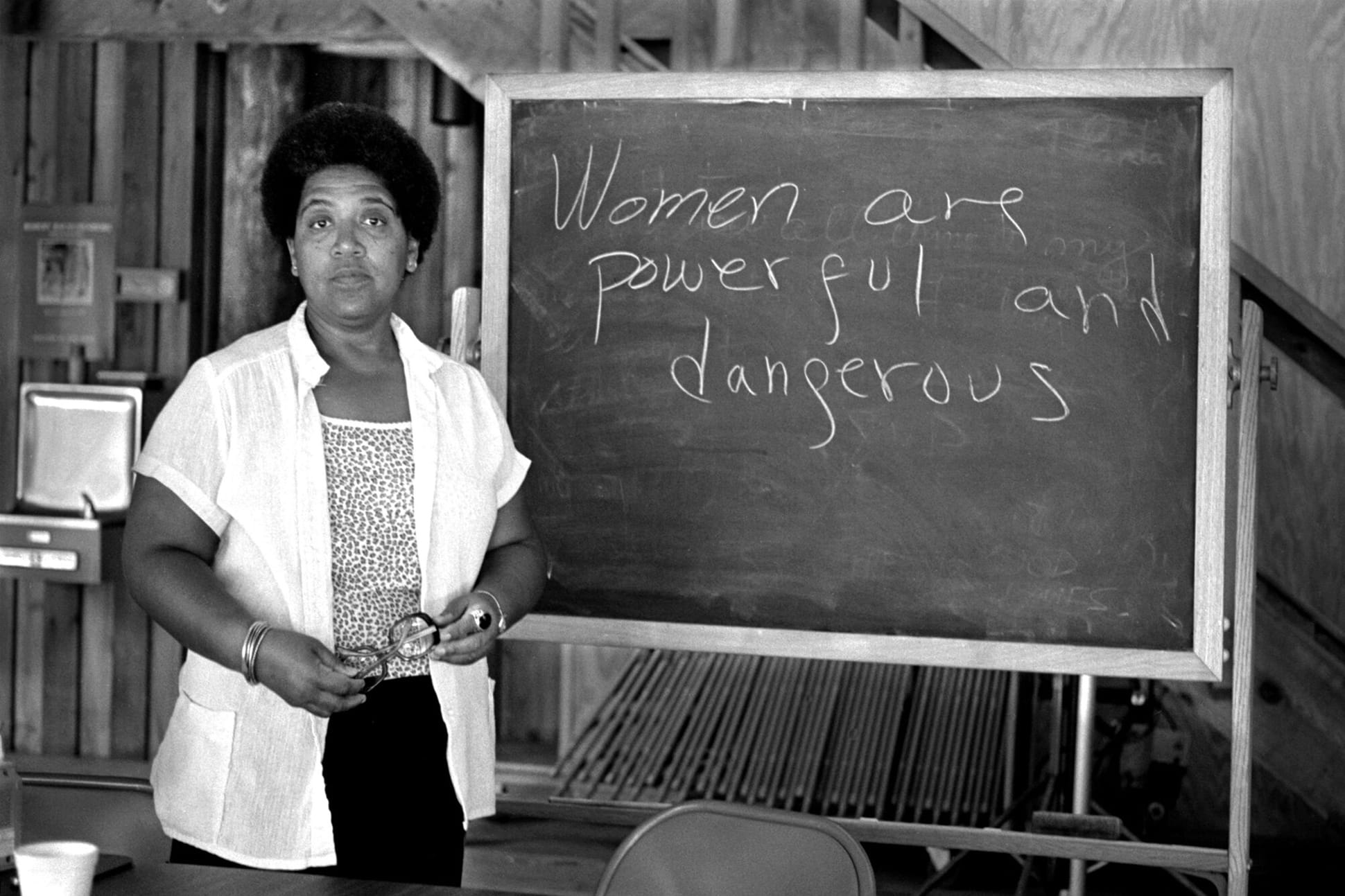

Audre Lorde (1934–1992) was a Black feminist, lesbian, poet, mother, and warrior. She was a native New Yorker and the daughter of Caribbean immigrants. Through her writing and activism, she advocated for the liberation of oppressed peoples and for organizing to occur across differences of race, gender, sexual orientation, age, class, and ability. In 1980, she co-founded the Kitchen Table: Women of Color Press alongside others, including Barbara Smith and Cherríe Moraga. She published several sacred texts, including “Uses of the Erotic: The Erotic As Power” (1981) and Sister Outsider: Essays and Speeches (1984).

Author: developer

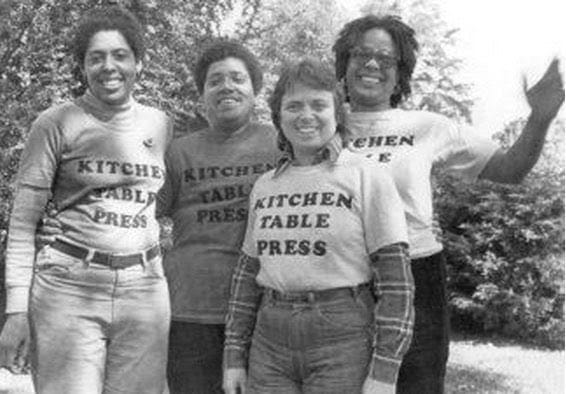

Kitchen Table Press

In 1980, activist, feminist, writer, and scholar Barbara Smith started a press to promote the writing, culture, and history of women of color. She chose the name Kitchen Table because it represents a central, intimate, and purposeful gathering place in a home. In her own words, the kitchen table is “the center of the home, the place where women in particular work and communicate with each other.”

National Black United Front

Founded in Brooklyn in 1979, the National Black United Front works to organize Black people around issues including police brutality, electoral campaigns, and the death penalty.

Beverly Guy-Sheftall

Beverly Guy-Sheftall is a Black feminist scholar, writer, editor, and the Anna Julia Cooper Professor of Women’s Studies and English at Spelman College. Guy-Sheftall has published a number of texts within African American and Women’s Studies, which include the first anthology on Black women’s literature, Sturdy Black Bridges: Visions of Black Women in Literature (Doubleday, 1979), which she coedited with Roseann P. Bell and Bettye Parker Smith.

Womanism

In 1979, Alice Walker coined the term womanist in her short story “Coming Apart.” In her book In Search of Our Mothers’ Gardens, she defined womanist as:

1. From womanish. (Opp. of “girlish,” i.e., frivolous, irresponsible, not serious.) A Black feminist or feminist of color. From the Black folk expression of mothers to female children, “you acting womanish,” i.e., like a woman. Usually referring to outrageous, audacious, courageous, or willful behavior. Wanting to know more and in greater depth than is considered “good” for one. Interested in grown-up doings. Acting grown up. Being grown up. Interchangeable with another Black folk expression: “You trying to be grown.” Responsible. In charge. Serious.

2. Also: A woman who loves other women, sexually and/or nonsexually. Appreciates and prefers women’s culture, women’s emotional flexibility (values tears as natural counterbalance of laughter), and women’s strength. Sometimes loves individual men, sexually and/or nonsexually. Committed to survival and wholeness of entire people, male and female. Not a separatist, except periodically, for health. Traditionally a universalist, as in: “Mama, why are we brown, pink, and yellow, and our cousins are white, beige, and black?” Answer: “Well, you know the colored race is just like a flower garden, with every color flower represented.” Traditionally capable, as in: “Mama, I’m walking to Canada and I’m taking you and a bunch of other slaves with me.” Reply: “It wouldn’t be the first time.”

3. Loves music. Loves dance. Loves the moon. Loves the Spirit. Loves love and food and roundness. Loves struggle. Loves the Folk. Loves herself. Regardless.

4. Womanist is to feminist as purple is to lavender.

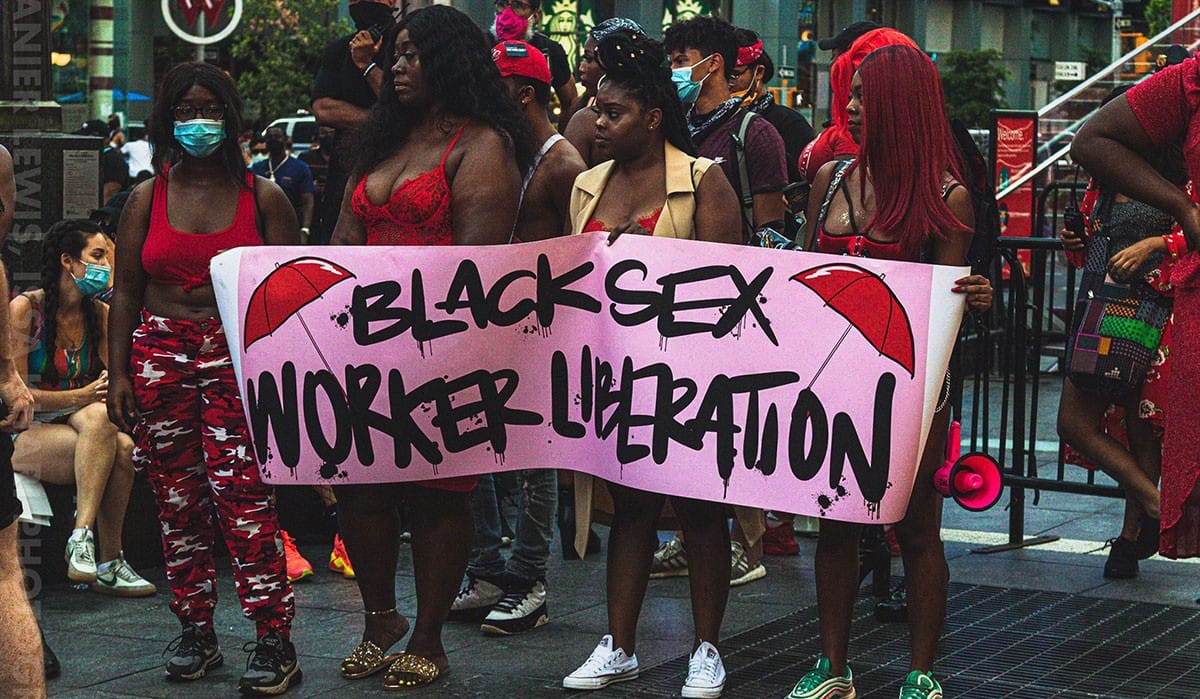

Sex Worker Rights

There is a long, powerful history of sex workers advocating for their rights. In the 1960s, sex workers were involved in key action points like the Compton Cafeteria Riot and the Stonewall uprising. However, it is said that the movement did not formally begin until 1978, when activist Carol Leigh coined the term sex work. The movement is centered on ensuring that “sex workers are entitled to live free of discrimination, stigma, and violence. As [with] all people, their rights to life, health, privacy, and bodily autonomy should not be infringed upon.” Many organizers and organizations involved in the sex worker rights movement focus on decriminalization efforts.

“Uses of the Erotic,” by Audre Lorde

In 1978, Audre Lorde published her timeless essay, “Uses of the Erotic,” which asserts that the erotic is a source of knowledge, power, and transformation. Lorde asserts that the erotic is a vital life force and a source of deep satisfaction, fulfillment, and joy.

Black Macho and the Myth of the Superwoman, by Michele Wallace

Michele Wallace’s book Black Macho and the Myth of the Superwoman (Verso, 1978) describes how women remained marginalized by the patriarchal culture of the Black Power movement, demonstrating the ways in which a genuine female subjectivity was blocked by the traditional myths of Black womanhood.

Pat Parker

Pat Parker was an activist and poet. She was the author of five poetry collections: Jonestown and other Madness (Firebrand Books, 1985), Movement in Black (Diana Press, 1978), Woman Slaughter (Diana Press, 1978), Pit Stop (Women’s Press Collective, 1975), and Child of Myself (Women’s Press Collective, 1972). She courageously addressed such topics as alcoholism, sex, race, and motherhood. She was the director of the Feminist Women’s Health Center in Oakland, California, and the founder of the Black Women’s Revolutionary Council and the Women’s Press Collective.

Loretta Ross

Loretta Ross is a feminist, activist, professor, and leader in the fight for reproductive justice for women of color. She is a co-founder of SisterSong and was their national coordinator from 2005–2012. In 1977, Ross and a group of Black and brown women coined the term women of color. She was also part of the group of Black women who coined the term reproductive justice in 1994 and consequently transformed reproductive politics in the U.S. She was one of the first Black women to direct a rape crisis center in the 1970s.